Marfa, Texas Restores Segregated School Built for Mexican Americans

In perhaps a first for Texas education history, Mexican American residents of Marfa, Texas have initiated an important community project: restoring their “Mexican” school built in 1909. Their intentions are that the creation of the Blackwell School Museum will shed light on an earlier historical period when equal educational opportunities were denied to Mexican American school children.

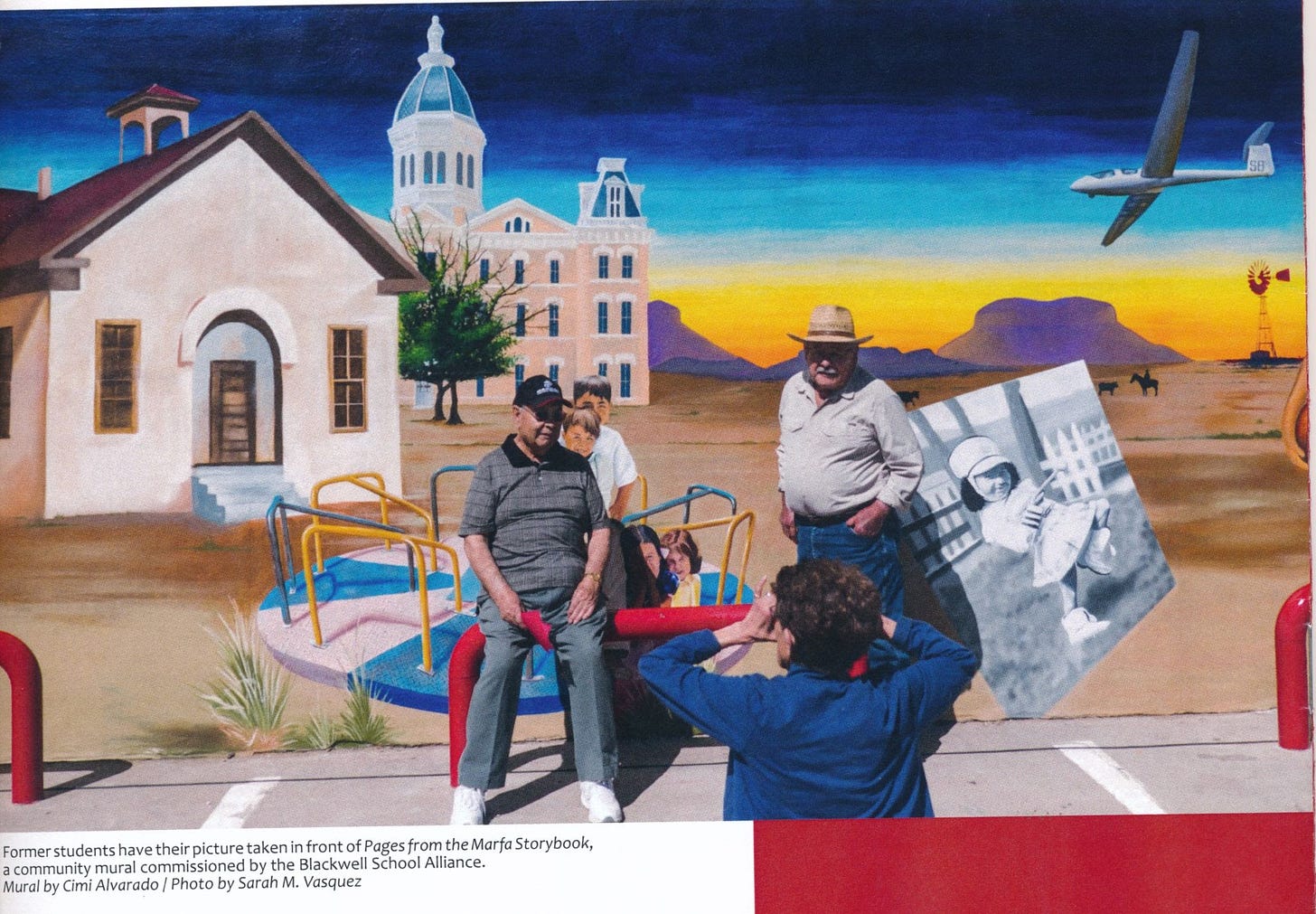

Photo courtesy of Gretel Enck, President of the Blackwell School Alliance. Photo by Sarah M. Vasquez

The Blackwell School in Marfa, Texas, one of the earliest segregated schools in West Texas, educated children of Mexican descent in the historic schoolhouse for nearly a half-century. The organizers of the effort to make this site a museum, all local community members, note that the Blackwell School today “serves as the portal to the collective memory of the students, educators, families, neighbors, and descendants of those who lived the experience of this school.”

In order to restore the school as a museum, the Marfa community has created the Blackwell School Alliance which is tasked with raising $1.4 million for the restoration and interpretation of the segregated school. William Dupont, The San Antonio Conservation Society Endowed Professor in the College of Architecture at UTSA and head of the Center for Cultural Sustainability is a consultant on the restoration project.

A Brief History of School Segregation in Texas

Mexican Americans first began attending segregated Texas schools in the late 19th century. For the most part, these schools persisted until the late 1940s when legal challenges to the segregation of Mexican American schoolchildren brought the separate “Mexican schools” to an end.

Perhaps the most famous “Mexican school” in American history is that of Cotulla, Texas where the future president of the United States, Lyndon B. Johnson, served as a teacher and principal. Historian Leininger Pycior, the author of LBJ & Mexican Americans, explained that segregation was founded on the belief among the Cotulla residents “that the Mexican majority should not have civic or social equality.”

When the U.S. Congress debated the issue of Mexican immigration during the mid-1920s, “segregation practices increased,” according to Pycior. For the entire first half of the 20th century, Pycior added, “Public accommodations throughout the Brush Country [South Texas] refused service to Mexicans or restricted them to the lunch counter or kitchen.”

While school segregation in Texas has a long history extending from the 1880s to the early 1960s, it has only been in recent years that historians have explored the rationale behind these policies and practices. We are indebted to several Tejano scholars: Guadalupe San Miguel, Arnoldo de Leon, David Montejano, and Cynthia Orozco for their studies of this topic. These scholars have helped explain why, when, and how local Texas school districts established “Mexican schools” in the years between 1880-1940.

Professor San Miguel wrote that by the end of the 19th century two distinct school patterns had emerged in Texas. With the exception of religious schools, principally Catholic and Protestant, most Texans did not have access to public schools. In rural communities, public schools were nearly non-existent. San Miguel added that “in the 1890s Mexican working-class children in urban areas were admitted to city schools. In both cases, access was limited to segregated classes in the elementary grades. No secondary or postsecondary facilities were available to them.”

Historian Arnoldo de Leon reported that for Mexican Americans and Blacks, “segregation existed in schools, churches, residential districts, and most public places such as restaurants, theaters, and barbershops.” Segregation, de Leon explained, “developed as a method of group control,” adding that most “Texas towns and cities had a ‘Negro quarter’ and a ‘Mexican quarter’.”

Historian Cynthia Orozco studied early segregation practices in Texas and found that from “1902 to 1940, especially after 1920, Texas school districts opened segregated schools for Hispanic children. By 1942–43 these schools were operated in 122 districts in fifty-nine counties throughout the state.”

In the early twentieth century, Tejanos faced discrimination on many fronts, including equal school access. In 1900 fewer than 18 percent of Mexican-American children ages five to seventeen were enrolled in public schools. By 1930 the number had increased to only 50 percent. [Guadalupe San Miguel]

The demise of school segregation for Mexican children began with a case in Del Rio in 1930 [Del Rio ISD v. Salvatierra]. Mexican American parents sued the school district for maintaining separate schools for Mexican American children. Cynthia Orozco noted that the newly created Mexican American organization LULAC provided the organizational and financial base for the movement against segregated schools, and the Del Rio case spurred the growth of LULAC.

The Del Rio Mexican American community lost its legal challenge, and scholars concluded that the Salvatierra ruling legalized the segregation of children of Mexican descent in schools through the third grade. The Mexican American community gained ground with the 1948 case, Delgado v. Bastrop ISD when a district judge ruled against the segregation of Mexican American children in the public school system.

With the passage of the monumental 1954 U.S. Supreme Court desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education, which dealt with separate schools for Black children, school segregation was declared illegal. Many West Texas school districts dragged their feet in fully implementing the integration of school children. Making the Blackwell School a National Historic Site will highlight a part of Texas history that has long been overlooked by the majority of Texans.

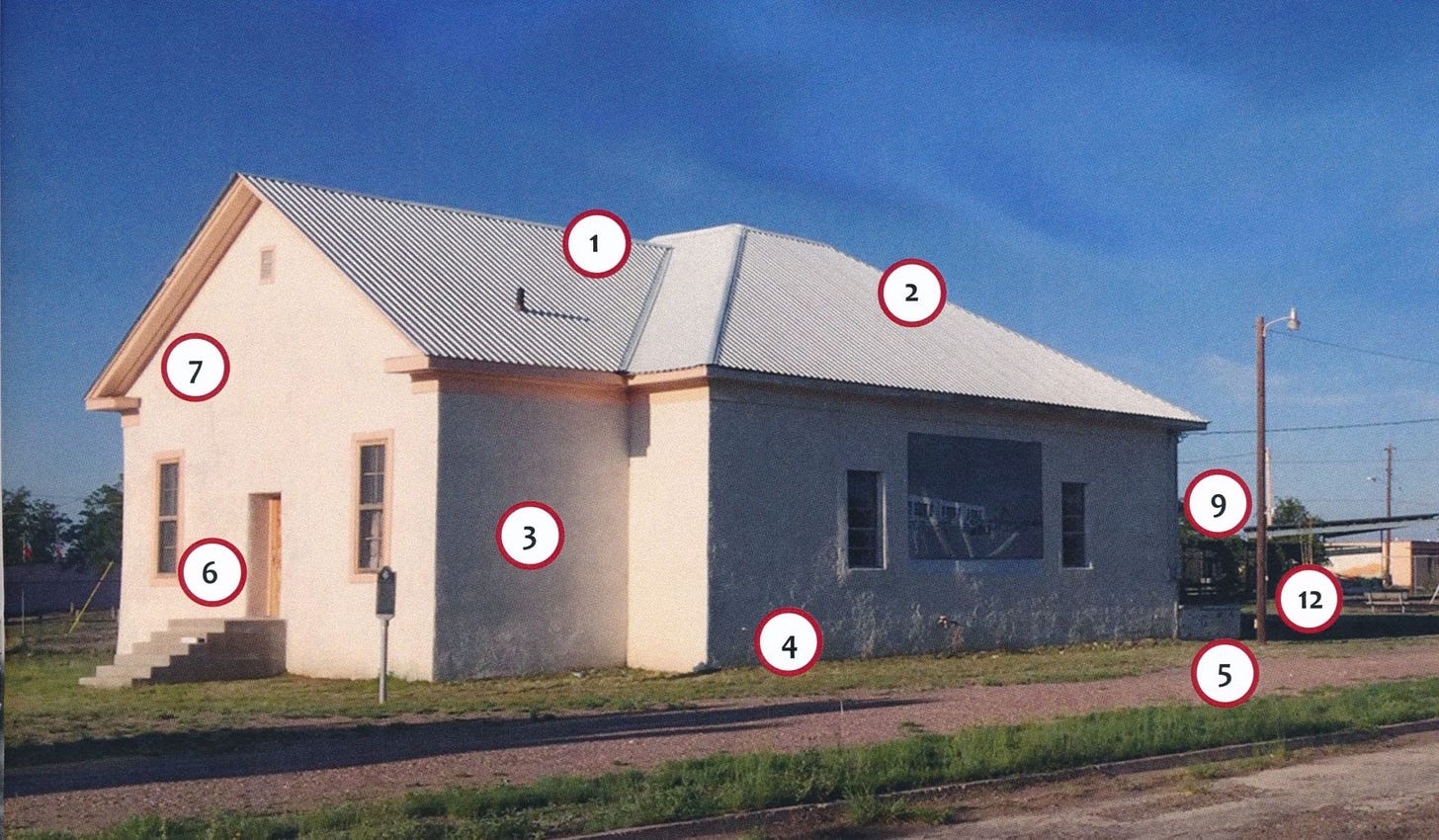

Blackwell School, Marfa, Texas. The Blackwell School Alliance.

The museum site intends to examine and showcase the historical significance and relevance of the Blackwell School to American and Texas history.

Blackwell School Alliance President Gretel Enck and the Blackwell School Alliance are raising matching funds to support the restoration of this important site. For more information about the project or to aid in this effort, contact: Gretel Enck, The Blackwell School Alliance, P.O. Box 417, Marfa, Tx. 79843.blackwellschoolmarfa@gmail.com