The apparition of the Virgin de Guadalupe on December 12, 1531 on the hills of Tepeyac, Mexico signaled the beginning of a new spiritual era in the Americas.

Raul Servin. “The 4 Ladies” From the Mexican Legends Series. Courtesy of Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

With the visitation of the Virgin, natives who had resisted Catholicism turned to the Brown Madona as their predominant symbol of inspiration and proof that God listened to them.

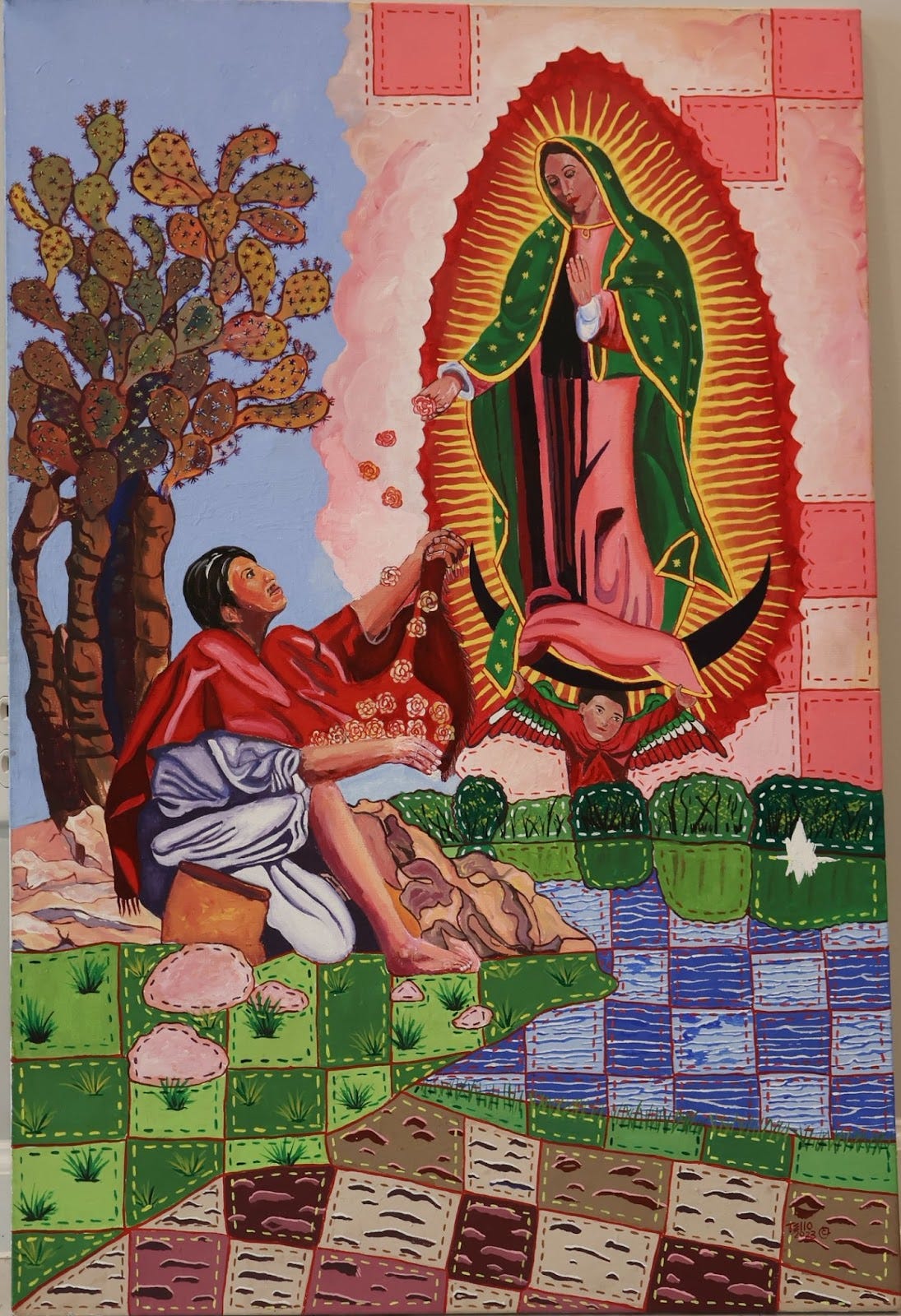

Victor Tello, “Second Apparation Southside Lions’ Park.” Courtesy of Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

In 1531, Mexico, Spain’s newest colony in the New World, faced crises on many fronts. Ten years after the conquest of the Aztec empire, the Spaniards continued to wage war on Indian communities. The region surrounding Mexico City, which had numbered 1.5 million inhabitants in 1521 when the conquistador Hernan Cortes defeated the Aztecs, had been devastated by war and epidemics that reduced the native Aztec population to 70,000 by 1531. Every year of forced work in the encomiendas and mines significantly shortened the lives of thousands of Indigenous people.

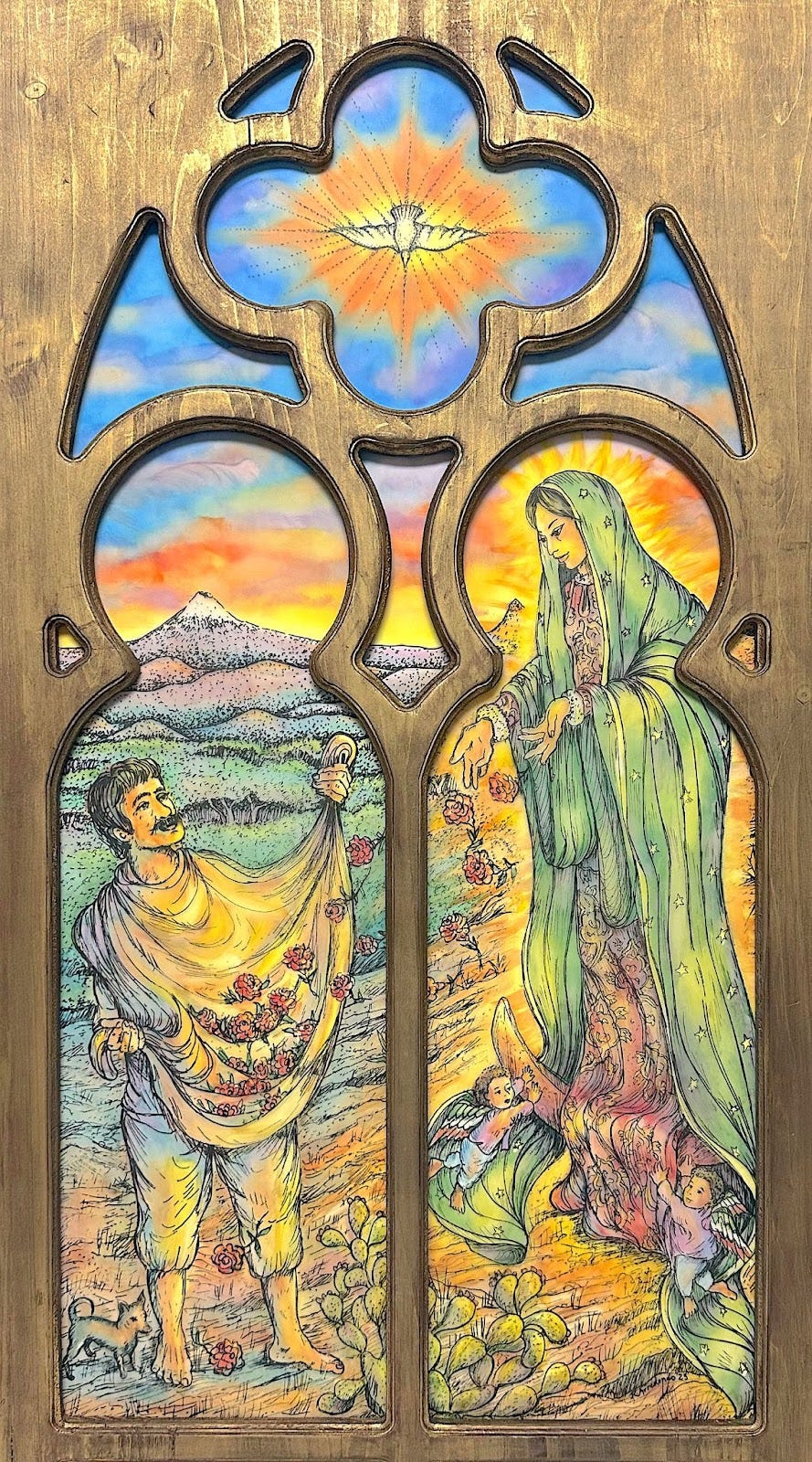

Richard Arredondo. Juan Diego Receiving Roses from the Virgin de Guadalupe. Courtesy of Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

Jacques Lafaye, author of Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe: The Formation of Mexican National Consciousness, noted that before the apparition, Catholic missionaries had little success converting the native population. Researchers also partially attributed this lack of success to their failure to teach natives the Spanish language. In their assimilation efforts, the friars created colleges and schools for native children. However, most Indian families rejected the idea of becoming “Spanish.” Moreover, Cortes had rewarded many of his soldiers with encomiendas, landed estates that came with free Indian labor, and the Indians were also required to pay tribute to the Hacendados.

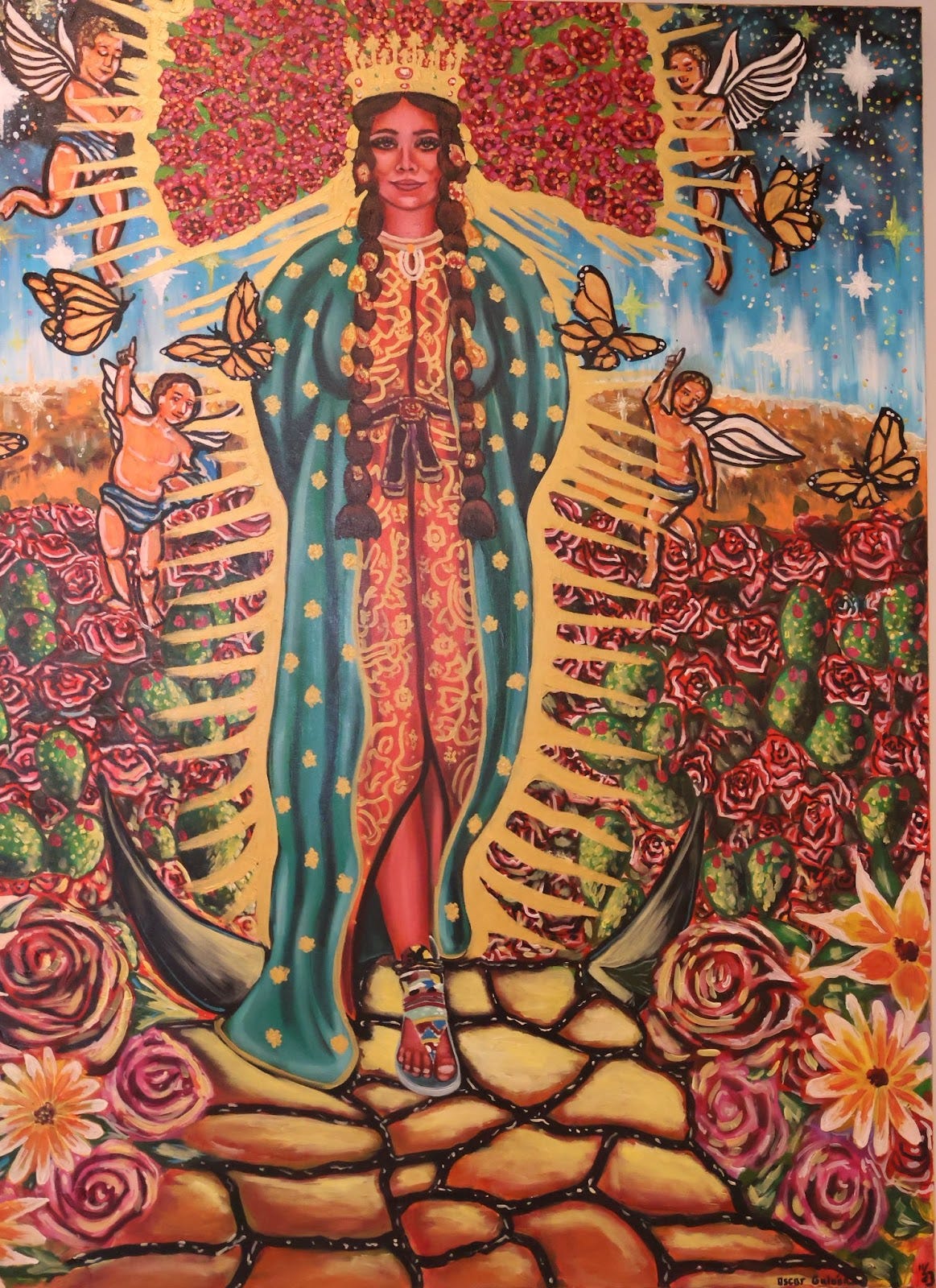

Oscar Galvan “En El Momento en que Escuche tu Voz.” Courtesy of Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

In addition to describing the Spanish failure to assimilate the native population, Lafaye argued that nation-building also required cultural harmony among the Spanish colonists regarding their identity. This thorny identity question was complicated by the arrogance of the initial Spaniards who arrived with Cortes. They considered themselves Spaniards first, people of the Iberian Penisula. They sought and held all the important government and religious posts in the conquered territory. In justifying their authority to govern, these Espanoles declared themselves superior to the Creoles, the children of Spanish parents born in Mexico. The Espanoles expressed condescending views of racial mixing and especially viewed themselves as superior to the Indians and those of mixed races.

Mauro Murillo. Painting of the Virgin de Guadalupe. Courtesy of Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

The spiritual chaos that plagued Mexico in 1530 had no precedent in the Americas. Mexico had the largest native population of the New World, and the Olmeca and Mayan civilizations were thousands of years old. The Aztecs had sophisticated religious rituals dating back to 1325 when they arrived in the Valley of Mexico. Moreover, the Spanish friars joined with the Royal armed forces in destroying all the native temples and constructing new Catholic churches in their place.

Alfredo Rodriguez’s Carved Virgin Guadalupe. Courtesy of Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

The story of the Virgin de Guadalupe began in December of 1531 when the Madona appeared four times to Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin on a hill in Tepeyac. Juan Diego informed Bishop Juan de Zumarraga that the Holy Mother had requested that a church be built on that site. The Bishop wanted proof that Juan Diego had talked to such a religious deity, and Juan Diego conveyed that request to the Virgin on December 12th. The Virgin asked Juan Diego to gather red roses from the hillside and deliver them to the Bishop. Juan Diego gathered the roses and placed them in his tilma [mantle of cotton fiber]. Upon opening his tilma to show the Bishop the roses, an image of the Virgin de Guadalupe appeared on the cloth. The Bishop was convinced by this miracle and ordered the construction of a basilica at the site where the Virgin first appeared.

The French intellectual Lafaye linked the apparition of the Virgin de Guadalupe to the emergence of a Mexican national consciousness. In essence, he viewed the incorporation of Catholicism made possible by the apparition not only as serving as a beginning of religious transformation but also as key to the formation of the Mexican nation.

Allison Schockner. Tapestry of the Virgin de Guadalupe. Courtesy of Centro Cultural Aztlan. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

In 1810, nearly three hundred years after the appearance of the Virgin, the Mexican colonists began their fight for independence from the Crown of Spain. Padre Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla from the parish in Dolores Hidalgo in Central Mexico led the rebel forces, mainly of Indian and Mestizo heritage. The ragtag army marched behind the banner of the Virgin de Guadalupe. In the aftermath of their victory, the first president of Mexico Manuel Felix Fernandez changed his name to Guadalupe Victoria. In 1829, Vicente Guerrero’s first act after being elected president of Mexico was to visit the Basilica built in 1531 to honor the Virgin de Guadalupe.

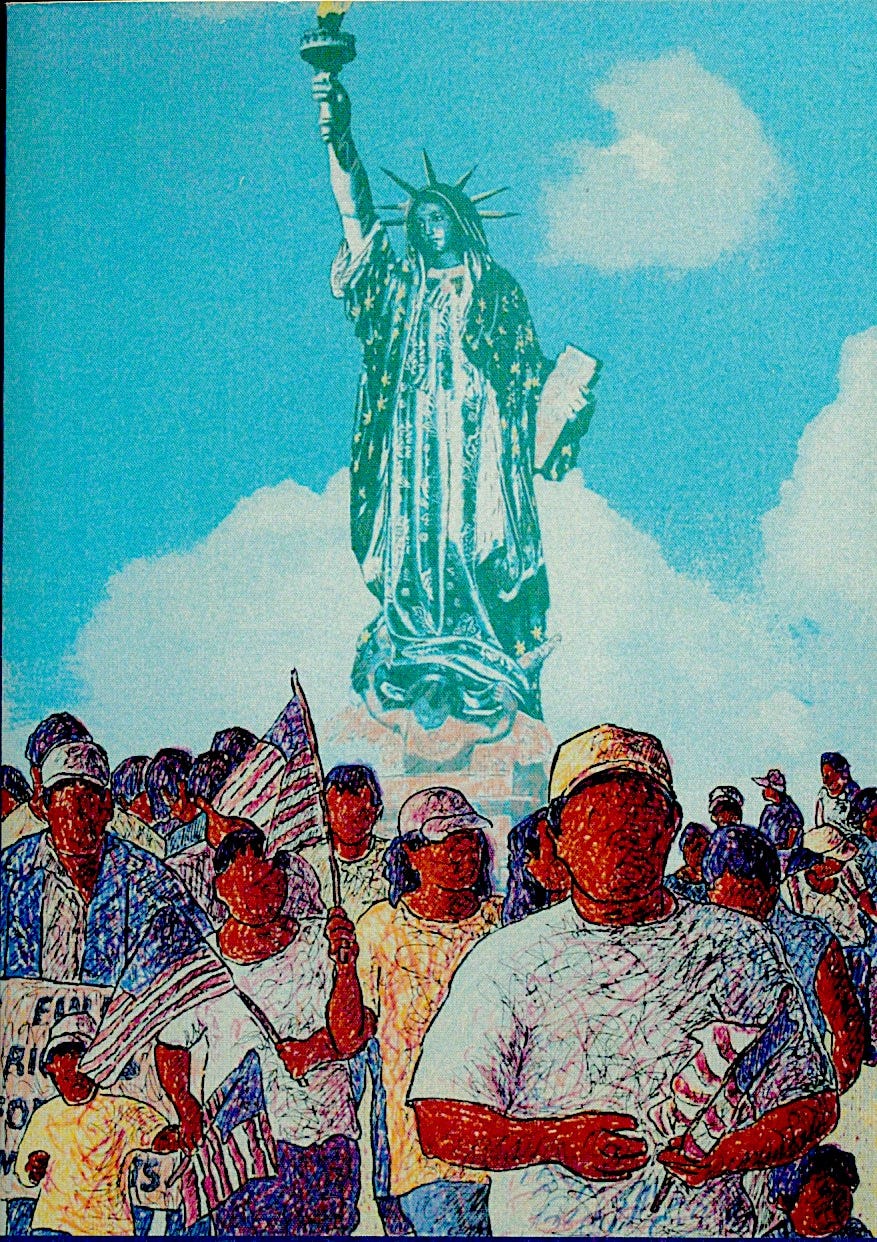

One hundred years later, almost to the date of the War of Independence, Emiliano Zapata led a rebel army consisting of largely exploited Indian rural laborers against the dictator Porfirio Diaz in the Mexican Revolution flying the banner of the Brown Madona. In 1965 in the US Southwest when Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta launched the United Farmworks [UFW] labor movement, farmworkers protesting labor conditions marched with the banner of the Mexican Virgin de Guadalupe.

Chicano Park mural, San Diego, Ca. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

The advent of the Chicano Art Movement coincided with the early years of the UFW movement. The first group of Chicano artists painted social justice murals on public walls in cities across the Southwest. Numerous artists completed a mural dedicated to the Virgin de Guadalupe. When my family and I visited Goetz Gallery in East Los Angeles in 1970, which is considered one of the first Chicano galleries in the United States, I recall seeing several paintings of the Virgin de Guadalupe demonstrating her powerful influence in the California Chicano community.

Tony Ortega. “La Marcha de Lupe Liberty.” Collection of Harriett and Ricardo Romo.

The veneration of the Brown Virgin grows every day. The Basilica dedicated to the Virgin de Guadalupe in Mexico City is the second most visited church in the world after the Vatican. In 2019, the Basilica in Mexico City recorded more than 11 million worshipers and visitors.

Sacred Heart Church in El Paso, Texas. City center for migrants and refugees. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

In full disclosure about my modest credentials in discussing this topic, I acknowledge that my Mestizo parents [both natives of San Antonio] were married at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church on El Paso Street in San Antonio’s Westside. I was also baptized at that same church and attended preschool religious classes at the Guadalupe Community Center five blocks from my residence on the Westside. In addition, our first home was on 2401 Guadalupe Street.

A beautiful mosaic sculpture of the Virgin de Guadalupe by Jesse Trevino is a block from this parish church. Murals in the city’s Latino communities frequently include images of the Brown Virgin demonstrating her continuing influence in Latino culture.

Centro Cultural Aztlan 28th Annual Celebration of La Virgen de Guadalupe Exhibit. Opening Reception December 12, 2023, 6 to 9 pm. 1800 Fredericksburg Rd. San Antonio, Texas, 78201.

Jesse Trevino, “La Veladora.” Guadalupe Cultural Center. Photo by Ricardo Romo.

Man! I love reading your “weekly” articles. I wish there were more, I’d binge read....

Beautiful work